The Stubborn American Who Brought Ice to the World

Before there was refrigeration, Frederic "The Ice King" Tudor figured out how to carve frozen water out of Massachusetts ponds and send it as far away as India.

Visitors to high-end bars during the last few years have witnessed a renaissance in ice. The cloudy half spheres that instantly melt are gone, replaced with clear ice carved from heavy blocks that hold their backbone longer. The bartenders at these places all seem to have Ph.D.s on the topic, waxing eloquent about surface area and density while charging you $15 for your drink. Those prices are a good reminder that for most of history, ice was an extravagant luxury only for the very rich. Today, machines make ice relatively cheaply so people can enjoy cool drinks and summertime hockey leagues. If you're in Dubai, you can even go downhill skiing indoors.

We can thank technology for the trickle down of many luxuries, but the transformation of ice from luxury to necessity largely occurred before the widespread availability of refrigeration. One man in particular, the Boston businessman Frederic "The Ice King" Tudor, engineered the change during the first half of the 1800s. Known for his pigheadedness as much as his marketing savvy, he revolutionized both the ice trade and the way we live.

Tudor wasn't the first to notice the value of ice, of course. The ancient Greeks, Romans, Persians, and Chinese all harvested and stored ice during winter to chill their food and drinks in summer. But with few exceptions, ice was reserved for the rich, and the ancient markets were relatively regional. Tudor's ice trade stood apart because of its sheer ambition: He believed that cutting ice from Massachusetts lakes and shipping it across the world to the tropics would make him "inevitably and unavoidably rich."

Most potential investors saw nothing inevitable or unavoidable about Tudor's vision. Instead, with their flinty New England gazes, they saw what historian Daniel Boorstin described as Tudor's "flamboyant, defiant, energetic, and sometimes reckless spirit." Yes, the market for ice was growing in the U.S., but wouldn't it just melt during a long voyage to the tropics? Their understanding of the science was accurate, and much of the ice Tudor shipped to Martinique and Cuba from 1806-1810 melted into large financial losses.

During each successive trip, however, Tudor learned to minimize melting by packing the ice tighter and insulating it with sawdust instead of straw. He made his first profits by 1810, only to be swindled by a business partner and land in debtor's prison. After Tudor was released, he secured a loan enabling him to continue with his obsession, but significant profits were still another 15 years away.

Tudor first sold his ice to scientists and physicians in the tropics who saw its potential for preserving food and for medical uses. He later expanded the market to cafes and wealthy private households for chilling drinks. Like a drug dealer, Tudor at first gave away his ice for free, then charged once people were hooked. After people tried their drinks cold, they could "never be presented with them warm again," Tudor wrote.

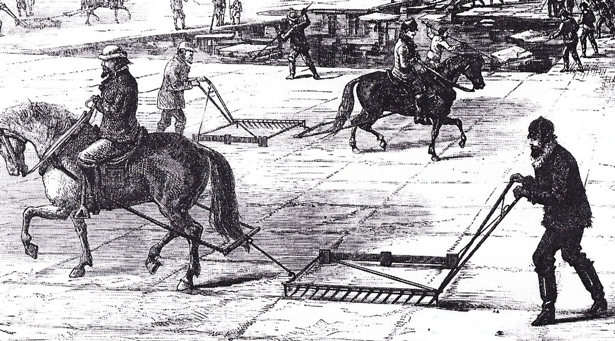

Tudor's increasing success led to the hiring of a new foreman named Nathaniel Wyeth to help meet growing demand. At that point, ice was laboriously cut by hand with saws. Wyeth developed a horse-drawn ice plough and a system where frozen bodies of water could be divided into chessboard patterns and cut into ice blocks about two feet square. This mass-produced ice was easier to transport and store, reducing Tudor's costs by two-thirds and enabling him to sell to a greater portion of the public.

Tudor's most ambitious plan came in 1833, when he set out to deliver ice to Calcutta, a voyage of 14,000 miles that involved crossing the equator twice. Tudor and his investors wondered if the ice would even sell. But his extraordinary profits answered that question. Until that time, residents had been importing slush from the mountains for the few weeks during the year when it was available. The prospect of a steady supply of Tudor's clear, solid blocks prompted English residents in the city to throw parties serving claret and beer chilled with his New England ice. The India Gazette thanked him for making "this luxury accessible, by its abundance and cheapness."

By that point, Tudor's success had drawn competition to the ice trade. Henry David Thoureau chronicled the growing industry near his Walden outpost, describing one stack of ice as "an obelisk designed to pierce the clouds." The ice symbolized an increasingly complicated world breaking from its preindustrial past, and a luxurious counterpoint to his experiment in simplicity. Besides, Thoreau didn't appreciate having his peace disrupted. He couldn't help but marvel, however, that "the pure Walden water is mingled with the sacred water of the Ganges."

By that time, Thoreau's fellow Americans were developing a taste for ice cream and iced drinks, German immigrants brewed lager beer year-round, and fisherman stayed at sea longer with their catches packed in ice. Across the ocean, the British Royal Navy, in pursuit of empire, was using imported ice to cool its gun turrets.

The ability to preserve perishables with ice also meant that food could be sold in the distant markets of America's fast-growing cities. Ice was becoming integral to daily life, and newspapers followed the ice trade closely. Unseasonably warm winters prompted warnings of "ice famines," and ice harvesters would sail to the Arctic and make up the shortfall by chopping up icebergs.

The vast majority of the trade was still natural ice, even though people had known for centuries how to artificially cool things. The ancient saltpeter-cooling approach was eventually followed by techniques that included freezing mixtures of salts and mineral acids. But these other methods were expensive and didn't make ice as well as nature did. Even though the British had advanced artificial refrigeration, Queen Victoria still got her ice from Massachusetts.

Artificial ice was only used in places where natural ice was almost impossible to get. This included the American South after it was cut off from the northern ice trade during the Civil War. The Confederacy's hospitals needed ice, and the South convinced France to send it ice-making technology that utilized an ammonia-and-water absorption process. Artificial ice became more popular after the Civil War, when cities expanded and intruded on the places where natural ice was harvested. Pollution had been a threat to the natural ice trade far before artificial refrigeration came along, but now it started causing health scares. Nonetheless, natural ice dominated into the early 20th century, but artificial ice was substituted where it made sense.

In 1883, Mark Twain described in Life on the Mississippi how manufactured ice was replacing natural ice near New Orleans. His description is a picture of decadence: The blocks were "crystal clear, within their icy depths big bouquets of fresh, brilliant tropical flowers." The ice sat on tables "to cool the tropical air; and also to be ornamental, for the flowers imprisoned in them could be seen as though through plate-glass'." But the luxury was now within reach of the masses. Twain compared the ice to jewelry previously available only to the rich but now worn by everybody. Ice had become commonplace.

Fast-forward more than a century to today's fancy bar. Bartenders have made ice extravagant again by "turning back the clock" and using the kind of ice Tudor sold, according to Charles Joly, Beverage Director at The Aviary in Chicago. The Aviary even employs a full-time "ice guy" who uses a Clinebell machine to produce 300-pound blocks of clear, dense ice like those cut from Massachusetts ponds years ago. The Aviary's drinks use ice to play on sight and sound as well as taste, Joly explains. The bar's "In the Rocks" cocktail contains a drink held inside an ice shell that explodes when opened by a slingshot, evoking the same excitement of the flowers trapped inside Twain's ice. Tudor would be stunned at where his ambition has led, and probably find it pretty cool.